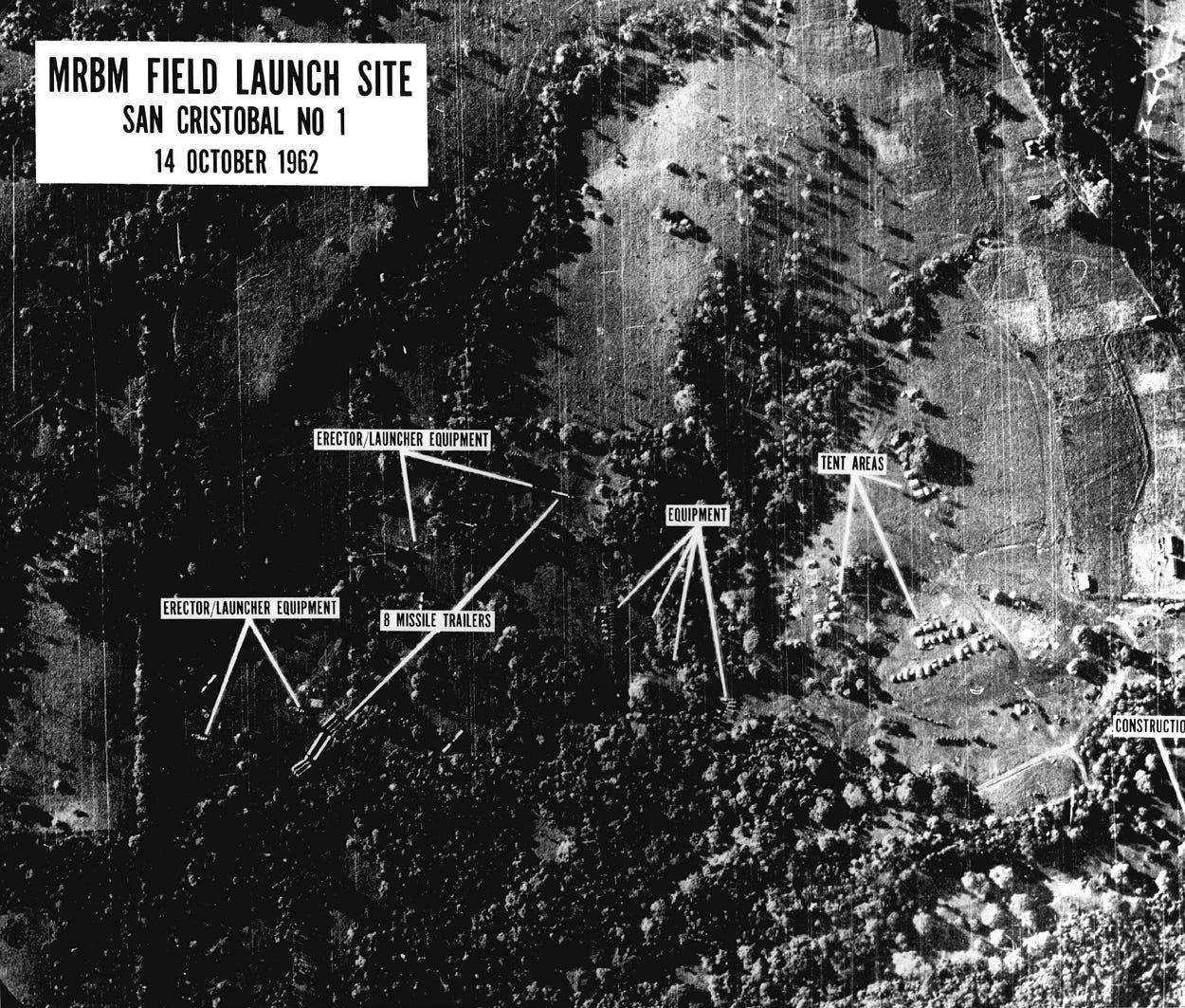

On a crisp autumn morning, October 16, 1962, the world unknowingly tiptoed on the delicate tightrope that separated existence from annihilation. It was on this seminal day that President John F. Kennedy received the ominous briefing: Soviet missile bases were under brisk construction on the Caribbean island of Cuba, mere minutes away in missile flight time from the American mainland. This revelation was the harbinger of the Cuban Missile Crisis, a 13-day geopolitical ballet marked by a precarious equipoise between aggression and restraint, between annihilation and survival.

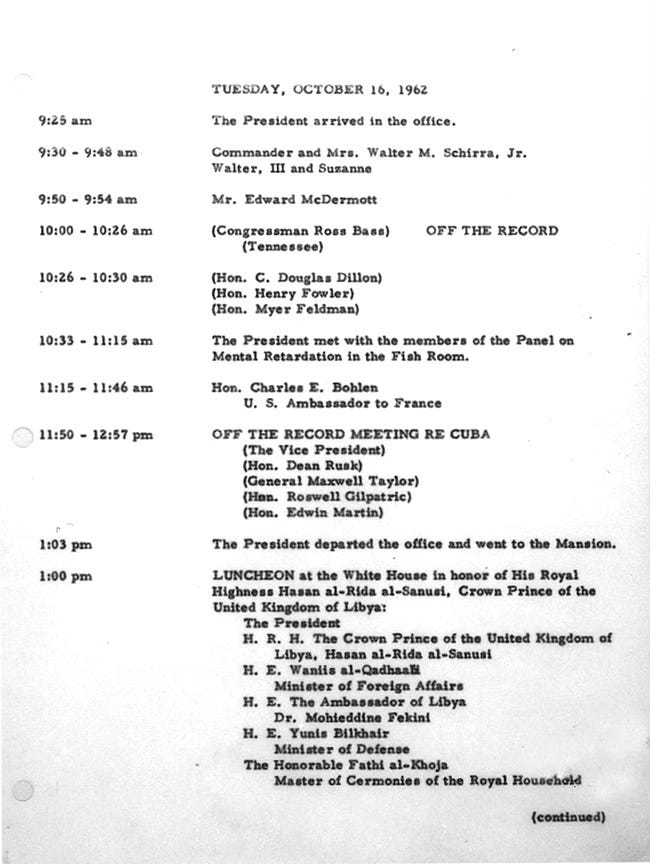

As the first light of dawn brushed the Washington sky, President Kennedy convened his coterie of advisors, an assembly that would later be known as ExComm - the Executive Committee of the National Security Council. The stakes were mountainous; a wrong move could trigger a nuclear apocalypse, an unforgiving rain of death that could extinguish millions of lives in a matter of moments.

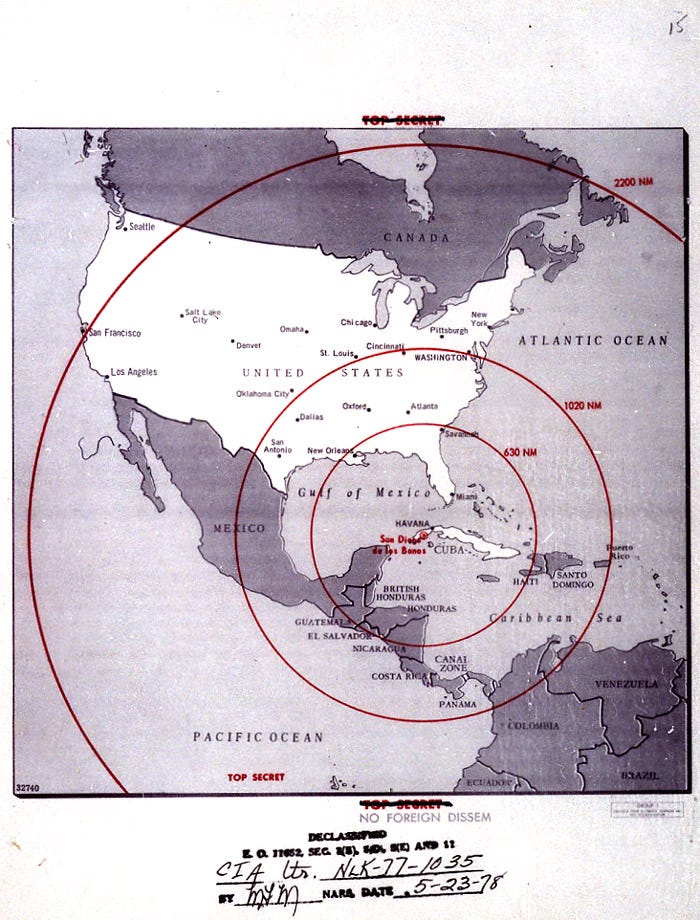

An exhibition of the terrifying potential of nuclear weaponry, which had mushroomed in the arsenals of the superpowers post World War II. The Soviet Union, under the stewardship of Nikita Khrushchev, had orchestrated this perilous chess move, ostensibly to deter a future invasion of Cuba by the United States, and to level the nuclear playing field which was heavily tilted in favor of the US.

The ensuing narrative of the Cuban Missile Crisis is a riveting tale of brinkmanship, of diplomatic acumen wielded amidst a cauldron of existential dread. The world watched with bated breath as the superpowers engaged in a perilous dance of death. The United States enforced a naval blockade around Cuba, a move that could be interpreted as an act of war. Yet, it was through the crucible of crisis that diplomacy emerged as the unsung hero. Secret negotiations ensued, a direct hotline between Kennedy and Khrushchev was established, fostering a back-channel dialogue that paved the way for a potential détente.

In one of their clandestine communications, Kennedy articulated the gravity of the situation, "It is insane that two men, sitting on opposite sides of the world, should be able to decide to bring an end to civilization.” This reflection underscored the monumental responsibility resting on their shoulders.

Kennedy's agreement to dismantle American missile bases in Turkey, juxtaposed with Khrushchev's acquiescence to dismantle the Soviet installations in Cuba, showcased the quintessence of diplomatic adroitness. The quid pro quo, albeit veiled in secrecy, was a testament to the potential of negotiation even under the most dire of circumstances. The world exhaled a collective sigh of relief on October 28, 1962, as the crisis was defused, averting a cataclysmic nuclear confrontation.

The Cuban Missile Crisis is a seminal chapter in the annals of modern history, a grim reminder of the apocalyptic potential nestled in nuclear arsenals, and a testament to the indispensable value of diplomacy in navigating the treacherous waters of geopolitics. This episode etched an indelible mark on the psyche of nations, catalyzing a slow yet discernible shift towards arms control, which would eventually culminate in landmark agreements like the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty.

The tale of those tense October days is not just a narrative of geopolitical maneuvering; it's a story of humanity standing on the brink, peering into the abyss, and choosing life over a nuclear winter. Through the lens of hindsight, the Cuban Missile Crisis, a narrative replete with lessons that resonate with profound relevance in today’s uncertain world, underscores the perennial necessity of diplomatic finesse and the unyielding spirit of hope, even when faced with the specter of apocalypse.

As the dust settled post-crisis, the political reverberations were felt on both sides of the Iron Curtain. Kennedy's firm but measured response bolstered his image domestically and internationally, portraying him as a capable leader in the face of existential threats. On the other hand, Khrushchev's political standing took a hit, leading to his ousting in 1964, a stark reminder of the high-stakes game of nuclear diplomacy.

The global populace, initially oblivious to the high-level negotiations, was later made privy to the near-apocalyptic encounter through declassified documents and revelations. The collective sigh of relief was coupled with a newfound cognizance of the fragile thread by which global peace hung, an awakening that underscored the quintessential role of diplomacy in the nuclear age.

I'm afraid this was only possible because of the type of person Khrushchev was. Putin is smart enough to understand that annihilation is bad, but I don't see him putting his ego aside in the interest of not annihilating the planet. The ego is just too important.